The music production industry has a gender problem – here’s how we can fix it

Written by WOM writer on July 4, 2023

Emily Lazar, Pops Roberts, Annie Rew Shaw and Lizzy Ellis discuss the issues highlighted by the recent Fix The Mix report and how change can be made.

“I’m not going to stop until it’s done,” says Grammy Award-winning mastering engineer Emily Lazar. “You want more women? Hire them. It’s not hard, and it’s not rocket science.”

The New Yorker and audio legend is talking about Fix The Mix, the report she commissioned through her pro-femme foundation We Are Moving The Needle. It’s becoming a key part of Lazar’s campaigning work to address the lack of work opportunities and visibility for women and non-binary producers and engineers, specifically in terms of their technical credits on top-charting releases.

“There are so many important facts revealed through the report,” she says. “When the money is being made and the awards are being given out, women and non-binary people are almost invisible.”

Illustration by Yordanka Poleganova

Illustration by Yordanka Poleganova

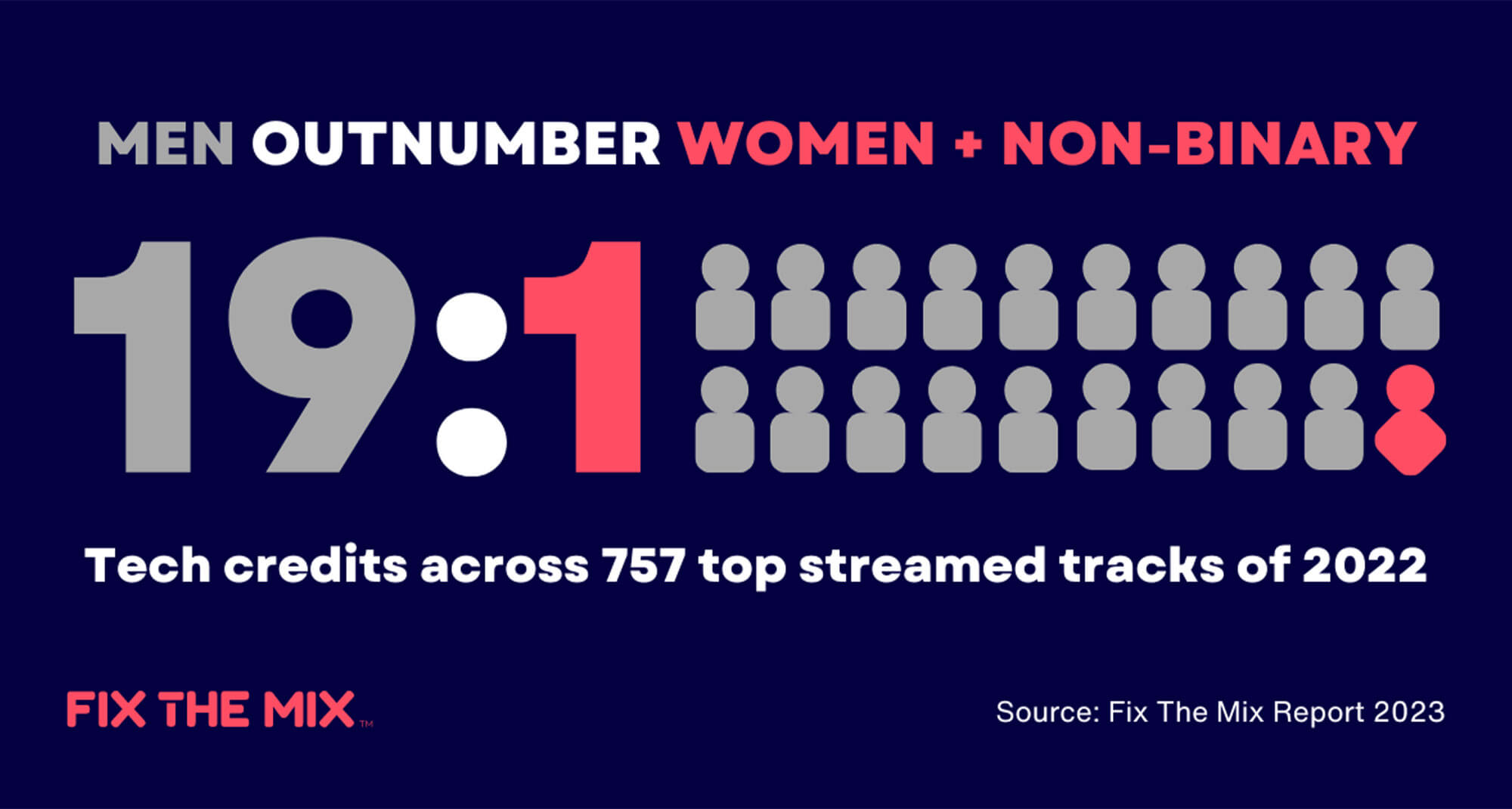

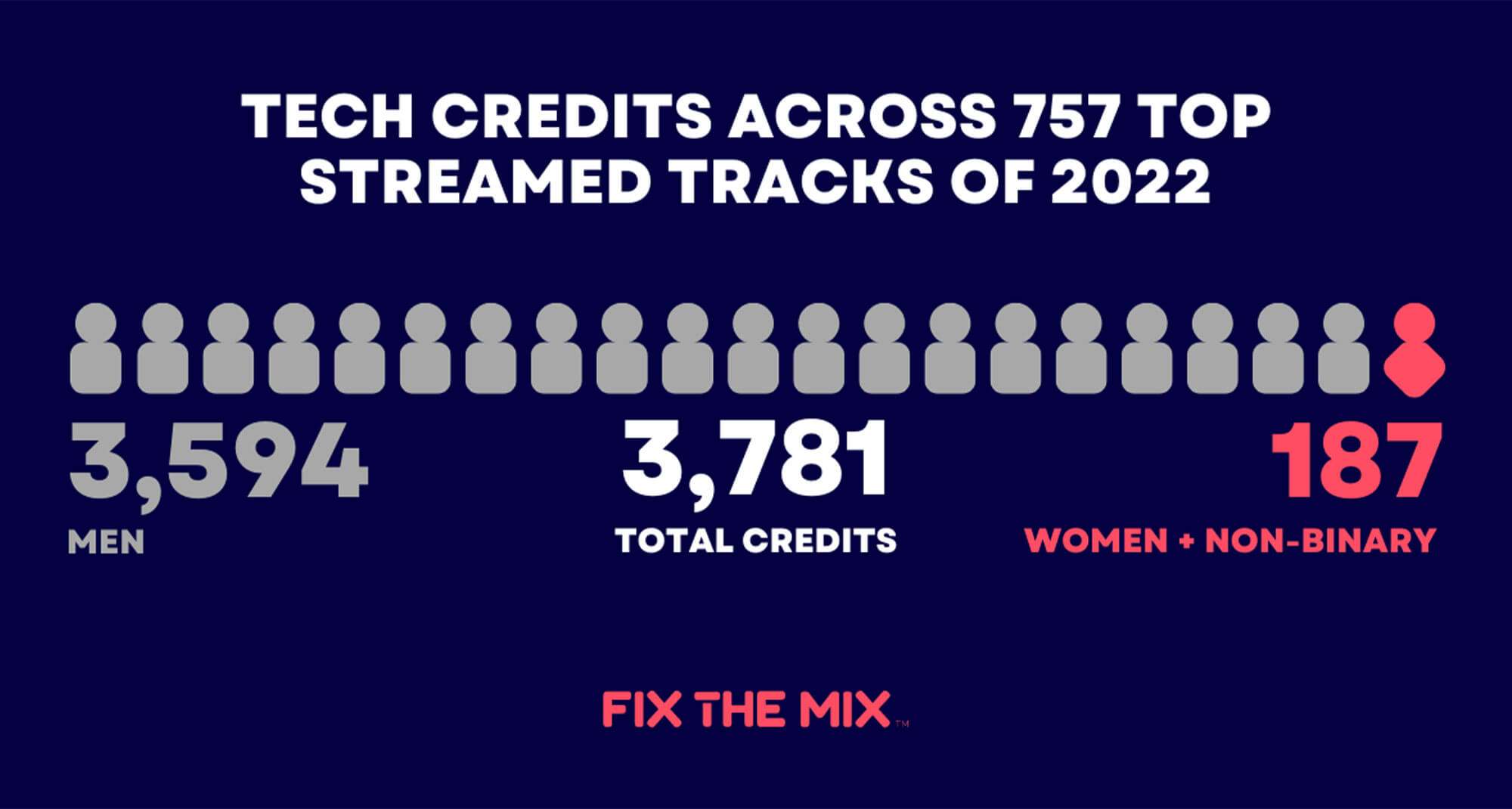

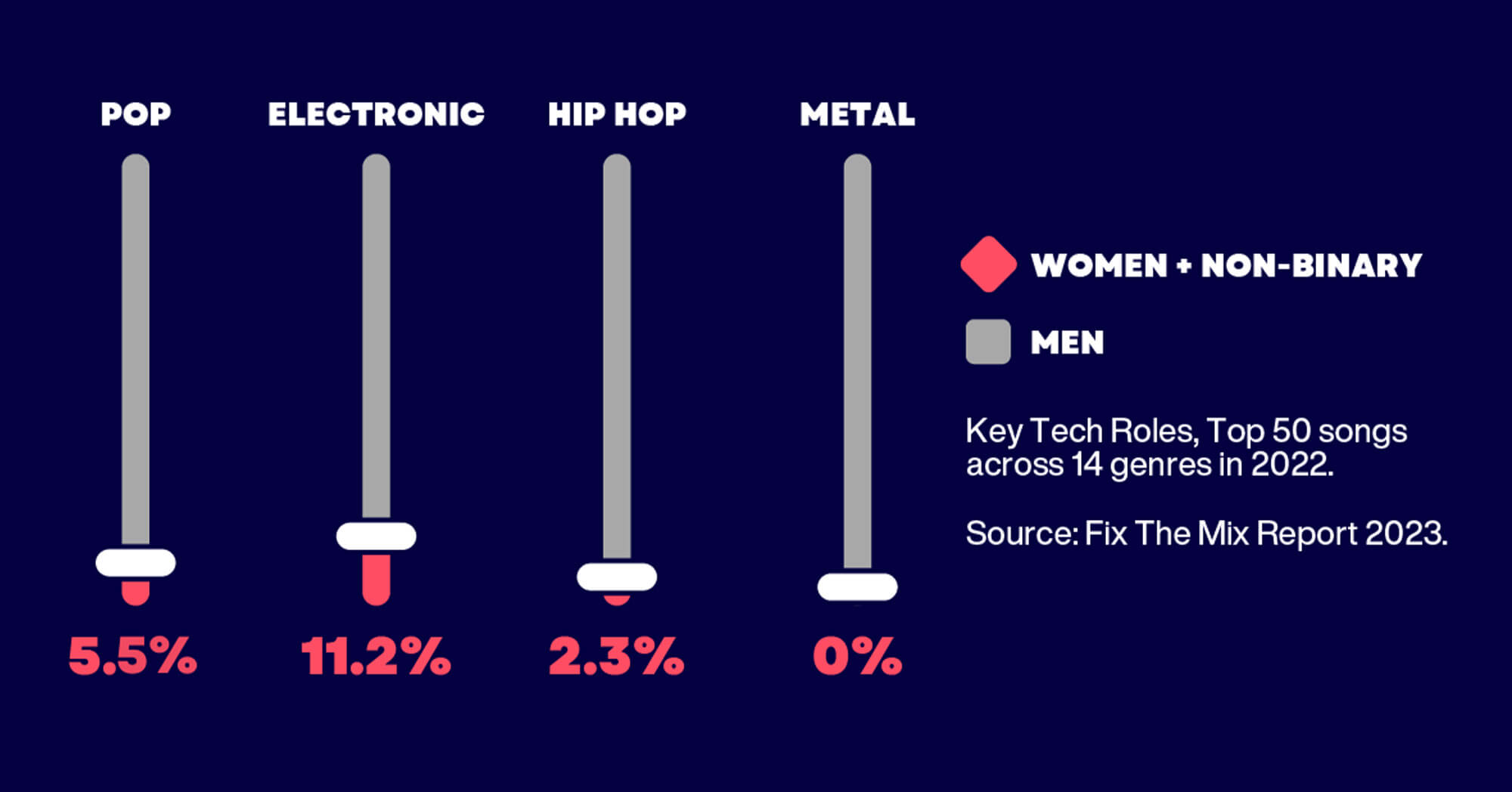

The report data was extracted from over 1,100 songs taken from top-ranking DSP playlists, Grammy-winning albums, plus Spotify and the RIAA’s top 50 all-time charts – the Billions Playlist and the Diamond Certified Records List, respectively. Then, stats were allocated by genre. This revealed some eyebrow-raising realities: at one end of the spectrum are electronic music and folk, both of which scored highest – a measly 11.2 per cent women and non-binary people are credited on top releases. Conversely, metal and Christian gospel both scored a fat zero per cent.

“The report illustrates in mathematical terms an indisputable, non-emotional picture of where we are now. It makes it easier to examine all the current initiatives and to measure their progress or lack thereof,” says Lazar, citing a $300m Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) budget shared across the three main US record labels. “Those zero per cent graphs are really important because they create this roadmap.”

Emily Lazar. Image: Press

Emily Lazar. Image: Press

Lazar’s work is a data-led version of other innovations occurring across the industry. A shining example is the Annenberg Report, which has been tracking diversity and inclusion in the music industry since 2017. Other creative responses to embedded inequalities include myriad grassroots organisations advocating for better representation industry-wide, including Saffron and Ladies Music Pub in the UK, plus Fix The Mix contributors and music credits database Jaxsta. Meanwhile, Audrey Golden’s recent book, I Thought I Heard You Speak, tells the story of iconic record label Factory through the words of the women who worked there – as a way of undoing the erasure of women’s work in and around music.

“One of the things people don’t always know is that this is part of my personal story,” says Lazar. “The anecdotes are real. My story is real. It’s why I founded Fix The Mix. This idea of being able to put data to those anecdotes is very important. It’s not just, ‘Oh I was the only woman in the room!’ No, I was the only woman in the room, and now there are facts to prove that. In other industries, that’s unacceptable. But for some reason, we’ve not had the data to prove this.”

Image: We Are Moving The Needle / Fix The Mix

Image: We Are Moving The Needle / Fix The Mix

A practical reason for the lack of data, Lazar says, is that many people who make records are freelancers who don’t have a union or organisation collecting information. In her words: “tracking who does what and letting people self-identity is important because it’s a super-disorganised group.”

Within the wider music industry, this isn’t a problem: “Every record label knows how many marketing people they have that are women or identify as non-binary,” she says. “They know within their companies who they’re hiring and there are quotas they have to meet. But not for the people who make the records – and this is a really important piece of the picture.”

Fix The Mix’s report team worked hard to ‘slice and dice this onion’ from as many angles as possible to maximise the data. “I believe the data is the key to solutions,” says Lazar.

“The other important thing is to prove that this is real and that nothing is going to change until we all come together to change things. Men, women, record labels, managers, accomplished producers, artists – anyone who is in a position of power to put together a team and to hire – we’re all responsible for the metrics we see and the metrics we’re going to see as everything gets better. Every choice is a chance to level the playing field.”

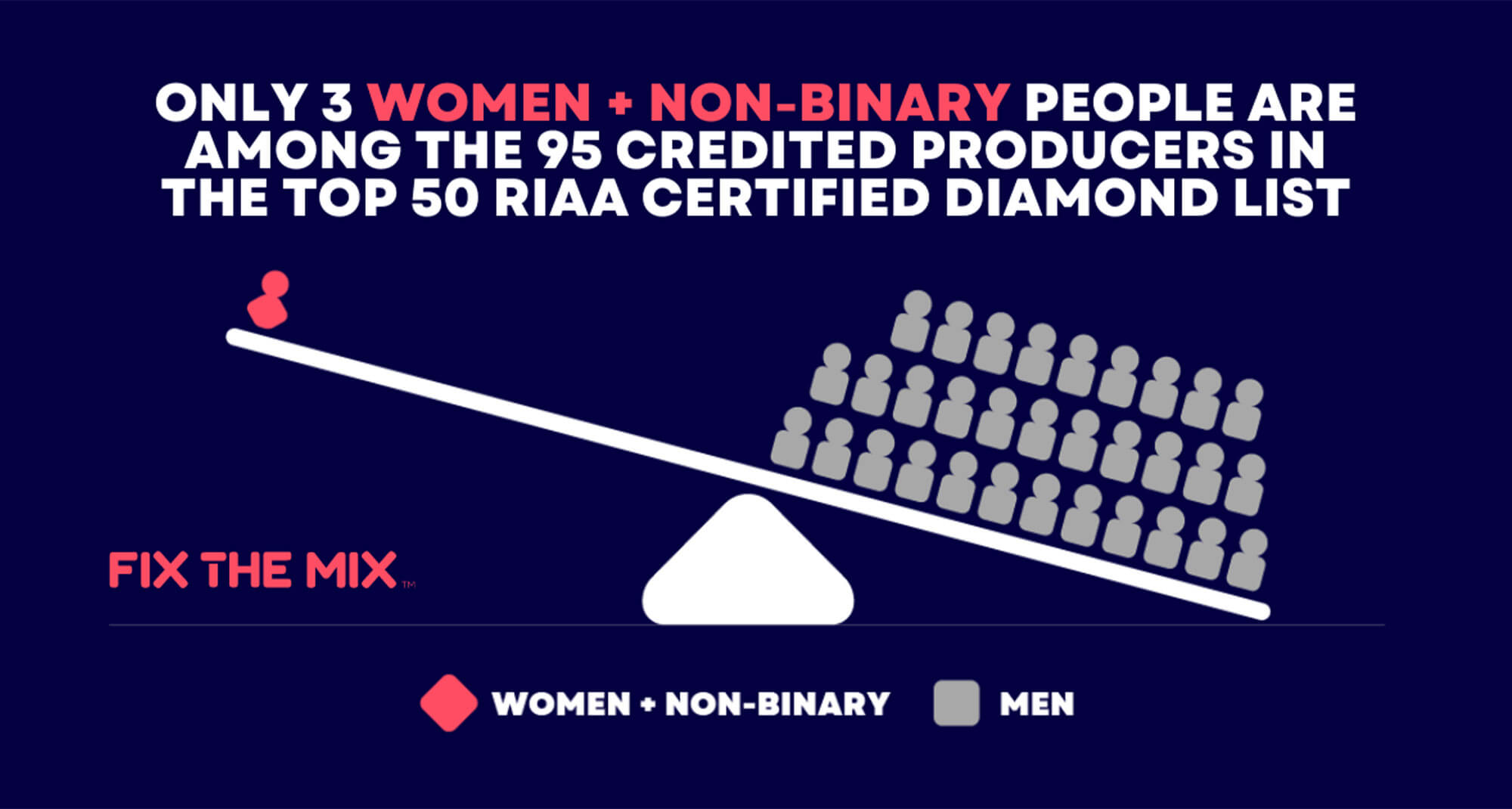

Image: We Are Moving The Needle / Fix The Mix

Image: We Are Moving The Needle / Fix The Mix

The playing field is full of potholes. Producer, vocalist and Certified Ableton Trainer Pops Roberts provides a neat example. A recent look through the various platforms where credits are logged for royalty purposes revealed that only one in five of her releases were properly registered.

“When I think about women or femme-presenting hurdles, I think of a lack of recognition,” says Roberts, who’s based in Manchester. “It’s not the artist, it’s usually a third party. Distribution or [another service provider] has just completely dismissed me because it’s a woman’s name on the paper. It’s always ‘oh sorry, it just got lost.’”

It’s a process that compounds – repeatedly – the inequalities that already exist; something she describes as “weaponised habitual carelessness.”

“I bet there are a lot of people who are on the mixdown or mastering side of things who aren’t getting credited properly.”

Pops Roberts

Pops Roberts

Other aspects contribute to the disparities. Roberts mentions the historic heaviness of technical kit and references a 2019 Guardian article about female sound engineers. “Now everything has been redesigned. Smaller gigs can rely on an iPad, not massive mixing desks. I think, previously, it was an excuse used by some men to justify why the tech side of the industry is male-dominated. Now you can’t deny that a woman is fine to lift an iPad and some amps.”

Working in production, engineering and mastering, adds Roberts, requires “a lot of nocturnal hours, which have been traditionally unsafe for women, in an unregulated space that’s dominated by men.” Though she predominantly teaches women, non-binary and femme-presenting people, she’s long found that her classes are also popular with men who demographically make up the music industry majority: “There are a lot of straight white men who wanted to hear my angle.”

Image: We Are Moving The Needle / Fix The Mix

Image: We Are Moving The Needle / Fix The Mix

Annie Rew Shaw is finishing her MA in Creative Music Production at the Institute of Contemporary Music Practice (ICMP) in North London. She’s had proximity to grassroots support throughout, initially when her friends set up online community 2% Rising for women, trans and non-binary producers.

“I’d always recorded my own music but never really credited myself as a producer,” she says. “2% Rising was a really supportive and encouraging space and, for the first time, I started to realise that this wasn’t just something I could do, it was something I had been doing for years.” This led to a place on Omnii Collectives 2021 Engineering Equality course and self-directed recording sessions at Small Pond Studios in Brighton, and eventually to a decision to apply for the MA. She’s primed to enter the workplace – but recognises that inequality also affects her potential earning power.

“It’s one thing having grassroots communities that serve to inspire and connect us with one another, but there is still a huge disparity in how much women are paid compared to men in the same industry roles.”

ICMP, she says, is actively hiring more female staff. But Rew Shaw is still one of only six women of 50 students on the course and, for the majority of the year, the only woman in her class – a dynamic which she describes as ‘isolating’. She believes there’s a missing link in the marketing, citing female students on the songwriting course telling her that they wanted to apply for production but didn’t know if they were skilled enough. “I know they’re skilled enough,” she says, “and I know they’d really benefit from the empowering nature of the course.”

Self-identification, she adds, is key: “Moving forward, I’ll always credit myself as producer, and if appropriate, mix engineer. But it took years of actually doing that work, being part of communities like 2% and getting an MA in the subject for me to feel confident to credit myself appropriately.”

Image: We Are Moving The Needle / Fix The Mix

Image: We Are Moving The Needle / Fix The Mix

The intersectional aspect of the music industry’s problem crediting women for technical roles is a key part of the work at Saffron, the Bristol-based music tech initiative dealing with music’s gender imbalance and which is currently running an emergency fundraiser after key grants were removed. Credits changing, says acting CEO Lizzy Ellis, are an ‘end result’ of the work they’re attempting. “These reports are only looking at the top end of the really commercial industry,” says Ellis “A lot of the grassroots stuff we’re doing is longer term. It’s about societal shifts around gender roles.”

The creative impact of reversing the poor picture revealed by Fix The Mix could be incredible, she adds. “That’s the key thing we get really excited about. What could music look and sound like when you have more women, non-binary and diverse people having creative control of the output?

“There are wider cultural implications that can’t be underestimated – having different people in studios, in writing rooms, and in the development and manufacturing of the music technology and creation tools, the software, the synths, which previously has 99 per cent been made by white men. In an environment that’s safer and more inclusive, artists could feel like they could make mistakes, could feel more free, and fully express themselves creatively.”

Saffron’s Lizzy Ellis. Image: Press

Saffron’s Lizzy Ellis. Image: Press

It’s a horizon that is increasingly appealing to music professionals of all gender expressions, even as the visual representation of studio life remains trenchantly old-fashioned. Pops Roberts says, “We need music videos showing women behind the dials. Every music video where they’re chilling in the studio, it’s all dudes. Or if there are women, they’re holding whatever vodka is sponsoring the video, inexplicably in a bikini in an indoor environment.”

Roberts describes a sense of relief within the demographic who’ve dominated the industry for decades. “I speak to a lot of my male friends in the music industry, who in the past have engaged in some of the male-dominated chatter that’s not very politically correct,” she says. “I hadn’t realised how many men I knew hated it, but were almost doing it because they’d been socialised to join in. They’ve got women in their lives who they don’t want to bring to the studio because they don’t want them to see that world.”

While Fix The Mix is aimed at today’s music industry, it’s also attempting to influence the next generation – and it’s starting young. The Amplitude youth programme is aimed at children aged nine to twelve years old. “We’re deliberately choosing to include boys,” explains Lazar. “We want to normalise equal representation and to make it visible for young women and non-binary kids to know what these careers are all about. And that little boy who is going to be a guitar player in a band? It’ll be totally normal for him to witness women in influential roles within the studio or as creators in the tech industry.”

This Autumn, Lazar will be announcing an allyship programme for people of all genders to offer themselves as ‘fairy godfathers and godmothers to usher in this change’.

“I cannot be responsible for this alone, right? The industry at large should be addressing this, and the people who are not the odd man out, the one and only lonely.”

In light of the Fix The Mix report, her basic ask is that anyone who can make change does so. And in some ways, it’s really as simple as her opening request – hire women. It’s not hard.

Emily Lazar’s work creating significant structural change is something she’s doing on top of her demanding day job mastering Grammy-level albums or top-flight spatialised audio at her recording facility The Lodge. No one asked her to do it, and she’s not being paid. So what does it cost her to do this additional work? “Sleep, personal resources, time,” she sighs. “The list goes on and on, but I would do it all over again if future generations of engineers didn’t have to go through what I had to go through in order to become established. We are moving the needle.”

Source: Emma Warren – musictech.com